Not unlike the churn of fast fashion, furniture is so disposable now

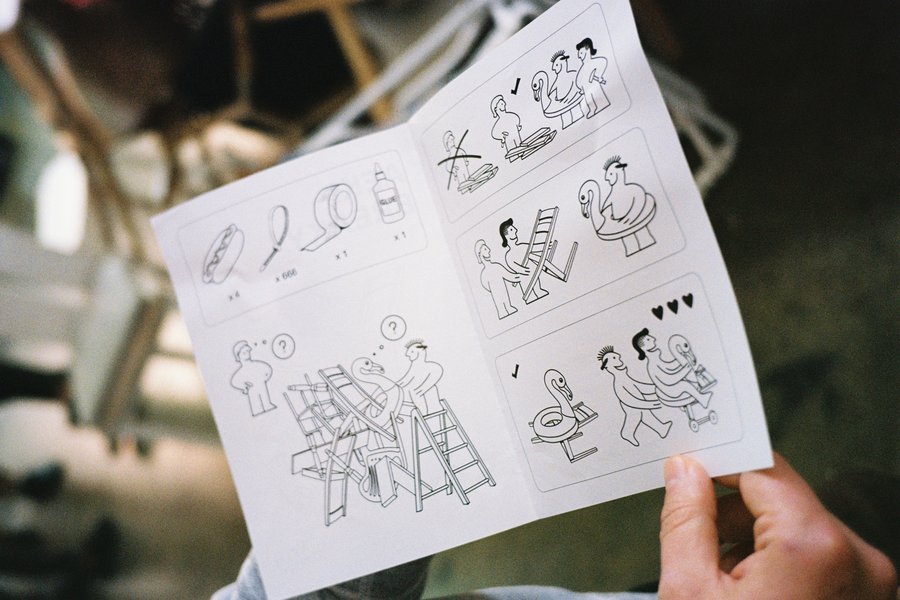

A month ago, I attended AEKI Breaky—The Reality of Fast Furniture, presented by The Dusty Road as part of Melbourne Design Week. These are the images from day one. A transformed Collingwood warehouse hosted a sculpture of broken furniture (referred to as original hard rubbish) with participants contributing to the evolving two day exhibition by deconstructing the installation and recreating largely conceptual furniture or sculpture. A reimagining of things that have fallen apart, AEKI Breaky leaned heavily on a tongue-in-cheek sense of humour mixed with blunt commentary on consumerism to explore the fundamental flaws of fast furniture and throw-away culture.

You see it on the berms. Office chairs with missing parts, shelving that is utterly unfit to support even its own form. Sofas. It is broken, and whoever cast it to the curb was hopeful that someone will collect it because they don’t want to pay to send it to landfill. Because that is the only place for it. There’s a lot of denial going on on many different levels: on climate change, on consumerism, class. It’s a big time for the world now. I suppose The Dusty Road would have been heartened to see participants make something beautiful out of that rubbish. They knew this would not be the case but rather an opportunity to communicate a relevant message to anyone in attendance to investigate the sentiment and thinking of cheap things.

It was in 2018 that I made my first investment in a Don Danart sofa bed and that was when I started to learn how to look for things. You would not find quality pieces in the Salvation Army and thrift stores anymore but you will on your local marketplace, on Facebook Marketplace. And if you could invest more, then retailers of mid-century modern. Anything designated “maker unknown” is an opportunity to pick up a piece that will undoubtedly be of higher quality than would come off a production line today. One thing about anything manufactured pre-1980s is that unless someone really decides to destroy it, that furniture will be around for a long time.

Most of my education had come from the Internet and some publications but I had also, when I had thought I might purchase an Eileen Gray Adjustable E1027 Side Table at around this time, subscribed to receive newsletters from the retailer Matisse. This is a store where one can purchase the Camaleonda® sofa system. Mario Bellini designed the Camaleonda in 1970 and manufactured it by B&B Italia in Italy. It has defined the aesthetics of an entire era of interior design. There was a newsletter sent that profiled the designer Patricia Urquiola, a renowned Spanish architect and designer who, while studying in Milan, was exposed to and influenced by some of the greatest names in twentieth-century design, such as Achille Castiglioni who emphasized processes such as reworking, restyling and using found designs. Included in the profile was this quote:

Now, unfortunately, “vintage” and “replica” have been weaponised by consumerism and the industry through brands and manufacturers who only wish to gain commercially, to make money from other people. It is easy nostalgic consumerism which is the root of mass-market commercial design intentions. I think there is much more to explore here, fake existences through social media being one. Diminished attitudes around ownership. Many people who purchased a replica classic Eames® Moulded Plastic Chair are the target of consumerist trends and disinterested, who do not document their identity through objects but through other people on Instagram. It is algorithm and influencer driven, that is the principle of current consumerist movements. Fitting in is important to the commercial consumer market. The business model of the world, not giving a shit about the supply chains, ethics, any of it. That’s affected the planet and all of these other things have affected our mental health.

We are kind of living in a “design for design’s sake” world. And when you wear fake style, it rubs off as fake—and it’s not necessarily totally the consumer’s fault, but it is a lot about education. The algorithm makes it difficult to find and get educated when the discovery feed is dictated by the mass. It is difficult to find the quality of anything. People included. Only when people are off the algorithm, when people are asking questions, being more intentional, will there be a rewiring and then perhaps we can overwhelm the algorithm, social media.

In an age of high-volume, manufactured products that are extremely affordable, it absolutely feels as if the middle ground has disappeared. Arguably there is a smaller pool of skilled labour as a result. Indeed, in the context of the environmental emergency, Urquiola’s approach was ahead of its time and could be way to make furniture for the future. Her work is even more poignant now in connection to the waste crisis, the climate crisis. But when the materials are so cheap, and unuseful it seems that if something was to change, it would need to be within the legislation, much like we are seeing with fast fashion in France, with reforms around electronics and the right to repair. Manufacturing should not be based on replicating the cheapest form of an aesthetic vision. It needs to be based on the company, the manufacturer’s dream of what is most efficient and least wasteful.